Systems Thinking

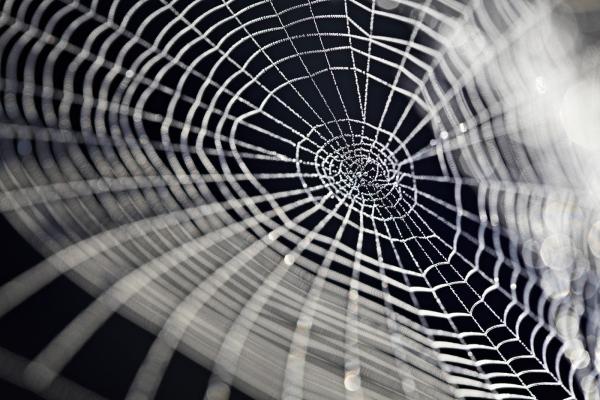

One lesson that nature teaches is that everything in the world is connected to other things.

John Muir famously wrote, "When we try to pick out anything by itself, we find it hitched to everything else in the universe."

A system is a set of interrelated elements that make a unified whole. Individual things—like plants, people, schools, watersheds, or economies—are themselves systems and at the same time cannot be fully understood apart from the larger systems in which they exist.

Systems thinking is an essential part of schooling for sustainability. A systems approach helps young people understand the complexity of the world around them and encourages them to think in terms of relationships, connectedness, and context.

SHIFTS IN PERCEPTION

Thinking systemically requires several shifts in perception, which lead in turn to different ways to teach, and to different ways to organize institutions and society. As articulated by Center cofounder Fritjof Capra, these shifts are not either/or alternatives, but rather movements along a continuum:

From parts to the whole

With any system, the whole is different from the sum of the individual parts. By shifting focus from the parts to the whole, we can better grasp the connections between the different elements. Instead of asking students to copy pictures of the parts of a honeybee, an art teacher takes her class to the school garden. There they draw bees within the context of their natural setting.

Similarly, the nature and quality of what students learn is strongly affected by the culture of the whole school, not just the individual classroom. This shift can also mean moving from single-subject curricula to integrated curricula.

From objects to relationships

In systems, the relationships between individual parts may be more important than the parts. An ecosystem is not just a collection of species, but includes living things interacting with each other and their nonliving environment.

In the systems view, the "objects" of study are networks of relationships. In the school or classroom, this perspective emphasizes relationship-based processes such as cooperation and consensus.

From objective knowledge to contextual knowledge

Shifting focus from the parts to the whole implies shifting from analytical thinking to contextual thinking. This shift may result in schools focusing on project-based learning instead of prescriptive curricula. It also encourages teachers to be facilitators and fellow learners alongside students, rather than experts dispensing knowledge.

From quantity to quality

Western science has often focused on things that can be measured and quantified. It has sometimes been implied that phenomena that can be measured and quantified are more important—and perhaps even that what cannot be measured and quantified doesn't exist at all.

Some aspects of systems, however, like the relationships in a food web, cannot be measured. Rather, they must be mapped. In the classroom, this shift can lead to more comprehensive forms of assessment than standardized tests.

From structure to process

Living systems develop and evolve. Understanding these systems requires a shift in focus from structure to processes such as evolution, renewal, and change.

In the classroom, this shift can mean that how students solve a problem is more important than getting the right answer. It may mean that the ways in which they make decisions are as important as the decisions.

From contents to patterns

Within systems, certain configurations of relationship appear again and again in patterns such as cycles and feedback loops. Understanding how a pattern works in one natural or social system helps us to understand other systems that manifest the same pattern.

For instance, understanding how flows of energy affect a natural ecosystem may illuminate how flows of information affect a social system.